3Rs implementation

|

If one needs animals for research must, first of all, verify whether it is possible to replace the animal model with an alternative method allowing to achieve the same result without employing animals (Replacement). If this is impossible, the second step consists in resorting to every possible mean to minimize the number of animals used, without affecting the robustness and validity of the result (Reduction). Finally, whatever species is used, animals must be treated with the most suitable available means to minimize the impact of the procedures on animals’ welfare and reducing as much as possible any form of distress or lasting harm possibly deriving from experimental procedures (Refinement). The “3Rs” have evolved over time, even if the basic principles are still the same and are now fully integrated into EU and italian laws on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. |

|

|

Replacement The general objective of the ongoing research projects is to understand the neuronal mechanisms underlying high-level motor and socio-cognitive functions expressed by a few other primate species, in addition to humans. The first and most obvious option for replacing animal models would be to study the same functions directly in human subjects. This is actually possible and several indirect, non-invasive techniques are widely used to study human brain activity, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, high density electroencephalogram, transcranial magnetic stimulation and magnetoencephalography. . Furthermore, in the last 20 years intracranial electroencephalographic monitoring has been more and more widely adopted for the pre-surgical localization of epileptogenic foci in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and negative magnetic resonance imaging examination: these primarily clinical studies make it necessary to resort to invasive techniques, offering the unprecedented opportunity to deepen our understanding of human brain functions (see for example1). Finally, the use of computational simulation models constitutes a further possibility for integrating collected experimental data and to formulate data-driven hypotheses and predictions: nonetheless, they requires direct experimental data. Together, these techniques greatly contributed to reduce the number of animals, particularly non-human primates (from 8000 to 6000 animals between 2008 and 2011 in Europe, corresponding to -25%, source: SCHEER report 2017) , used for neuroscientific research. However, none of these techniques to data available for human studies allows to entirely replace animal models for single cell and neuronal network studies, since none of these techniques allows the recording of the electrical activity of individual neurons. These studies, possibly carried out by simultaneous recordings from multiple brain regions, constitute the only way to causally understand the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying behaviours, linking single-cell and brain-network levels. This multidisciplinary and integrated approach has been developed, validated, and now it is widely employed in neuroscientific research in rodents2. In these models, several techniques, including genetic techniques, allow the manipulation of specific neuronal populations providing an unprecedented resolution in the study of the various levels – from molecules to single-neuron and brain networks – in which brain functioning is articulated3. The complexity of the behaviors studied in this project (fine manipulation skills, communication and social interaction, communicative gestures) makes it impossible to resort to species other than non-human primates. Among them, macaque monkeys represent the less neurologically developed species suitable for these studies. |

|

|

Macaque monkeys (Macaca fascicularis and mulatta) are also the most suitable species for biomedical and neuroscientific studies in general4 because they show the anatomo-functional, cognitive and behavioral homologies to humans that are necessary and sufficient to provide an evolutionary grounded, comparative understanding of the neurophysiological and behavioural mechanisms they share with humans5. Upper limb motor skills and the control of finger movements to reach and grasp objects, for example, relay on evolutionary preserved mechanisms and substrates6. In addition, macaques are the only animal model available for neuroscientific research in which it is possible to find a wide range of social and affiliative behaviors explicitly exhibited through body postures, motor behaviors, facial gestures and vocalizations, often combined, which therefore create a complex form of social communication at a multisensory level of incomparable complexity relative to those of rodents or other species at lower neurological development7. More specifically, Macaca mulatta is widely used in behavioral neurophysiology also for its excellent adaptability and tolerance to housing and laboratory conditions if managed and constantly controlled in a proper way8. Furthermore, it constitutes the most directly known and familiar species (compared, for example, to Macaca fascicularis) for the research group, whose members studied the biology and ethology of these animals in various neurophysiological research projects at the University of Parma, previously authorized by the Ministry of Health (Aut. Min. 128/2005-B and 129/2005-B of 20/9/2005, 60/2006-C and 61/2006-B of 20/4/2006, 207/2008-C of 24/11/2008, 54/2010-B and 55/2010-C of 18/3/2010, 294/2012-C of 11/12/2012), as well as during FELASA courses and in continuous interactions with colleagues from the other Primate Centers where Macaca mulatta is the most widely employed species in the neuroscientific field. |

Macaca mulatta |

|

Reduction In neuroscientific studies on non-numerate primates, experimental designs are not normally carried out between groups and the sample size is not defined in terms of animals, but on the basis of the number of independent measurements performed reliably and reproducibly on the individual animal. However, in the light of possible interindividual variability and to ensure not only the robustness but also the reproducibility of the findings, the demonstration of an effect similar to the one obtained in the first animal has to be reproduced in a second animal, according to the standards in the neurophysiological literature. Therefore, the minimum number of animals necessary and sufficient for each neurophysiological experiment typically correspond to two. The possibility of adopting new technologies to employ the same animals in different experiments (e.g. injection of pharmacologically active substances and neuroanatomy) will allow us both to improve the quality of the results and to reduce the number of animals necessary, without relevant impact in terms of “cumulative severity”.

The refinement of the procedures in non-human primate research represents not only an ethical and legal obligation but also a fundamental resource for increasing the compliance of animals with experimental conditions and hence for maximizing the quality of the collected data (see Refinement techniques in non-human primate neuroscientific research). All the procedures envisaged in these projects, from housing to surgical and experimental procedures, are optimized according to the highest international standards. The effort to permanently eliminate head-holding systems, moving towards the massive use of wireless recording technologies from freely moving animals, constitute crucial steps that go far beyond current standards and meets the recommendations of the most recent EU guidelines on this issue (see SCHEER report 2017). The animals are purchased from authorized suppliers, capable to guarantee the availability of animals born in captivity by parents born in captivity as well (the so-called second generation, or F2 animals – therefore no animal used or even its parents have been wild capture). The animals are always transported by trained and authorized personnel, with suitable means. Since their acquisition and arrival at our premises and facilities, the refinement measures for the animals taken by the personnel concern all aspects relevant to improve the animals’ “cumulative life-time experience”, from housing to experimental procedures, as follows. ▪ Training of the experimenters. The assessment, monitoring, and optimization of the environment and procedures during the entire lifetime of the animals can lead to substantial benefits only if they are managed by expert personnel, adequately trained to the purpose. For this reason, all scientific and technical personnel with direct responsibility for the procedures or the daily management of animals in the facility receive specific theoretical and practical training, demonstrated by the achievement of FELASA A and B certification specific for work with non-human primates in biomedical research before starting any interaction with animals. The continuous exchanges with the staff (colleagues and veterinarians) who work in other European primate centers is a source of continuous education and training, which adds to the periodic updating of the staff obtained through participation in seminars and specific events relating to the 3Rs and animal welfare. |

|

|

▪ Housing and enrichment. A system of linked cages compliant with European Directive 63/2010 (and with Italian Dlgs 26/2014), designed and built by a leading company in the sector in collaboration with the major European primate centers, hosts animals in pairs offering space greater than the minimum required by law (minimum 2.5 m3 per animal, against 1.8m3 required by current laws). The environment is managed according to a daily program of enrichment rotation which includes mirrors, various perforated objects for foraging, a substrate in sawdust or natural bark in which to disperse seeds and other small foods that the animals actively search during foraging, suspended toys and ropes. The cage system also includes a large “playroom” with a tree and a swing, which allow animals to climb and jump: each monkey pair can access the playroom according to a schedule allowing all the animals to express their full species-specific behavioral repertoire. There is a sound diffusion system and a large screen for the projection of videos, which constitute sensory and cognitive enrichment very appreciated by the animals. Several windows in the facility provide optimal natural illumination and contribute to maintain regular night/day cycles (in addition to a timer-controlled system of artificial illumination, which ensure the control of the day-light cycle by turning off the light in the night). An electronic temperature control and management system connected to alarm systems constantly active ensure optimal condition for primate housing. Sanitary management of the environment and daily feeding of the animals is carried out by the specialized technical personnel on the basis of the indications and with the collaboration of the research staff and the local contact person for animal welfare. |

|

|||

|

▪ Positive reinforcement learning. All animals are trained to interact with the experimenters and with the laboratory equipment already when they are in their home cage. We leverage the spontaneous exploratory tendency of these animals to apply computerized self-training techniques9 10, in the presence or absence of the scientific or technical staff, but in any case, always by means of positive reinforcement. The formal training to perform specific experimental tasks requires a period (whose duration is subject to interindividual variability) of familiarization with the experimenters: they start interacting with the monkey by giving it simple commands through the cage and reinforcing it with fruit and other palatable food upon request accomplishment. The food used for the training is typically constituted by fresh fruit or vegetable and fruit juice, in addition to the normal daily dry feed ration (which is always given in any case). The habituation procedures, likewise all the subsequent training procedures, are performed by trained personnel and using operant conditioning techniques based on positive reinforcement11. Clicker-training is systematically used to facilitate and accelerate the acquisition of new skills, by associating to correct behaviors an immediate acoustic consequence, which anticipates the delivery of the reward12 13. Animals destined to experimental project in which head fixation is still unavoidable are progressively trained to approach, enter, and remain in the primate chair for progressively longer time, but always moving independently from the cage to the chair and avoiding the use of rigid collar or leash14. All the methodologies employed in our project are based as much as possible on the animal’s willingness to actively cooperate in order to get extremely positive rewards, thus avoiding to add unnecessary stress to the animals with deprivation protocols and creating the best premises for the success of the subsequent experimental procedures in the laboratory.

This type of procedure can take up to 1 year, in particular because of the delicate phase of habituation of the animals to accept day-by-day the limited mobility on the primate chair: gradualness is necessary to avoid the risk of refusal to cooperate, which can always happen and implies to resume the training starting from a previous and steadily achieved step. The training of animals that do not need to receive an head-fixation system is simpler and faster: animals need only a few weeks to pass, generally without showing any signs of stress, discomfort or refusal to collaborate, from the cage to the transparent plexiglass carriers through which they can be transferred to the environment equipped for wireless recordings. The validation of these procedures and of wireless recording methodologies will allow to progressively eliminate completely the head-fixation systems and the primate chairs for a considerable number of studies, thus contributing substantially to the refinement of the procedures. The specific training for the tasks necessary for the experiments is performed in the same way, adopting structured behavioral methodologies such as task analysis, the identification of behavioral chunks composing the global behavior, the differential reinforcement of subsequent behaviors that are increasingly similar to the target one, shaping of the response and fade-out of cue stimuli used as intermediate steps for the more complex tasks. The general objective in these procedures consists in the selection, by means of positive reinforcement, of those behaviors among the entire animal’s behavioral repertoire that the animal is immediately able to display and that can be progressively shaped to correspond to the desired target behavior. In this way, the reinforcement of these behaviors and the concomitant extinction of the unwanted alternatives lead progressively to the emergence of skills that comply with task requests of considerable degree of complexity from a cognitive point of view. These techniques and procedures are exactly the same as those used by the best dog trainers and essentially apply to any animal species, including humans. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

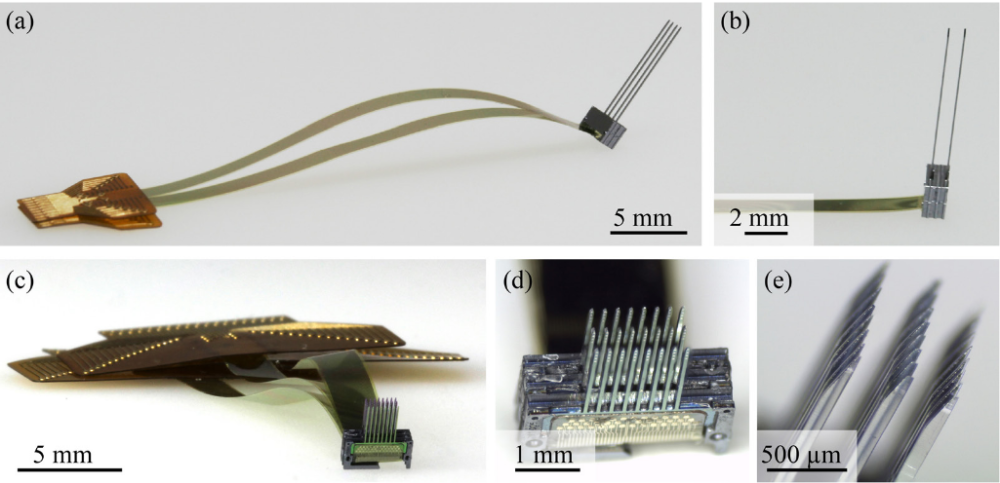

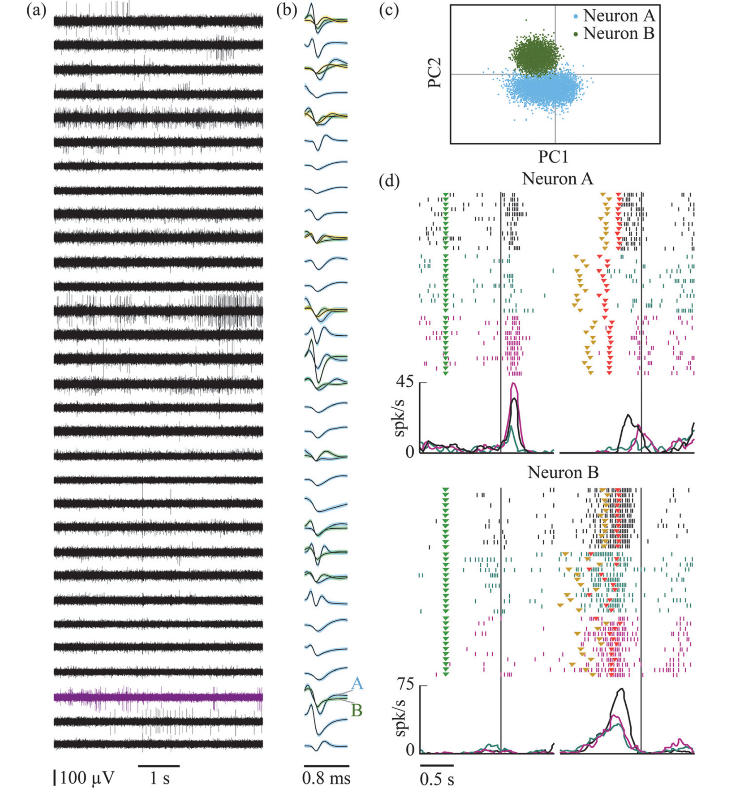

▪ Miniaturization and refinement of invasive devices. All the devices to be implanted surgically on animals (such as neural probes or the interconnection system for the wireless transmitter) are made of biocompatible materials, reducing as much as possible their size. The multielectrode probes have a diameter between 50 and 100µm, in order to cause negligible tissue damage as evidenced by histological analyzes conducted in a previous study15. The head-fixation devices, used only whenever strictly unavoidable, have proven to be well tolerated, showing excellent osteo-integration16 and no sanitary or welfare problem to the animals. |

|

|||

| ▪ Anesthetics, surgical techniques and post-operative pain medication. All major surgical procedures are performed in the presence of the designated veterinarian. General gas anesthesia with halogenate is performed and monitored by a veterinarian specialist with FELASA certification of competence for working with non-human primates and with extensive anesthesiological experience with different animal species, including primates. The intraoperative control of the main physiological parameters (temperature, respiratory rate, spirometry, partial oxygen saturation, heart rate, electrocardiographic monitoring and arterial pressure with non-invasive method) is guaranteed by a multi-parameter monitor managed by the veterinary. A neurosurgeon is available for supervision and consultation whenever necessary. Post-operative progress is monitored by the trained staff personnel, which are responsible for managing the animal under the direct supervision of the designated veterinarian and the anesthesiologist veterinarian, who prescribe drug therapy (antibiotic, anti-inflammatory and analgesics) to be administered in the following days of post-operative progress until complete recovery. |

|

|||

| ▪ Recording techniques that maximize the quantity and quality of collected data, reducing the number and duration of recording sessions. A further important element of refinement consists in optimizing the use of magnetic resonance imaging in anesthetized animals in order to obtain anatomical images of the morphology of the skull and of the brain. The 3D reconstruction of a plastic model of the skull of each animal allows to anatomically shape the devices to be implanted according to the specific conformation of individual monkey’s bone: the results obtained so far with this technique have shown the possibility to obtain implants that are lighter, less invasive and with not need of periodic disinfection, cleaning or maintenance operations, with considerable benefit for the animal welfare. The study of the individual brain’s anatomy, on the other hand, allows us to accurately identify the anatomical localization of the region of interest, and constitutes the basis for the possibility to use semi-permanent probes implanted precisely in the region of interest, optimizing success of the recordings and hence reducing considerably the number of the procedures relative to conventional acute approaches. Simultaneous multi-channel recording allows us to sample the activity from hundreds of brain sites simultaneously, using only a few probes with several recording sites along each slender shaft. The monitoring of behavioral parameters such as motion kinematics or ocular position can be carried out with totally non-invasive methodologies, based on infrared sensitive camera systems and special infrared light sources that allow to maintain maximum signal stability in all illumination conditions with light in the visible spectrum. |

|

| ▪ Use of the same animals for neurophysiological and neuroanatomical studies, without impact in terms of “cumulative-severity”. It is important to stress that the implantation of recording probes does not cause any significant brain tissue damage and consequently no suffering or behavioral deficit to the animal. Indeed, it is possible to use the same animal from which neuronal activity has been recorded to trace the anatomical connectivity of the investigated region. Neuroanatomical studies aimed at directly defining the connectivity of the electrophysiologically studied regions are carried out by implanting an “injectrode”, that is a recording probe identical to those used for the recordings. These “injectrodes” are silicone probes equipped with one or more microfluidic channels in their shank, through which it is possible to inject both small quantities (in the order of microliters) of pharmacologically active drug or, at the end of the experiments, neuronal tracers. The latter are transported retrogradely or antero-retrogradely and allow us, after an adequate period of axonal transport in relation to the injected tracer, to verify directly, post-mortem, the anatomical connectivity of the investigated region. Neuroanatomical studies, therefore, do not require any additional specific procedure relative to those already foreseen and described for neurophysiological studies, do not require “dedicated” animals and cannot produce significant additive effects in terms of “cumulative severity”. The animal is killed by painless euthanasia with the methods indicated by the law at the end of the neurophysiological experiments, in order to allow to reconstruct the anatomy and connections of the studied brain region. Importantly, the animals are always in excellent psycho-physical conditions at the time of euthanasia: no procedure can ever lead the animal to death. Euthanasia in fully healthy animals is necessary in may studies for the reconstruction of the anatomical properties and connections of the brain, which is impossible to obtain with any of the available non-invasive methodologies. Anatomical tractography techniques based on MRI (e.g. DTI) are still extremely coarse and lack sufficient precision, are not yet reliable and reproducible and in no way represent an alternative to neuroanatomical studies with tracers. This is the reason why in the ongoing projects there are currently no plans to rehome healthy animals at the end of the experiments. Nonetheless, as soon as the progress of the aforementioned non-invasive anatomical techniques will provide data of sufficient quality or in cases where the reconstruction of the anatomical network is not necessary, opportunities for rehoming animals at the end of the experiments will be seriously considered. |

|

| ▪ Continuous monitoring of animal welfare. In spite of the measures so far described, at any stage of the experiments it is possible to encounter adverse and unpredictable events impacting on animal welfare at different degrees. It should be noted that adverse events of various type (incidental trauma, wounds from conflict with the partner, transient infections or organic dysfunctions) can occur as for any other animal in the wild, in captivity or pet, even in the absence of any relationship with the experimental procedures themselves. To cope with the possible negative effects of these events, a further important general refinement measure consists in the constant monitoring of animal welfare by trained and qualified personnel using as a reference a special clinical evaluation form prepared, for each animal, at the time of its access to the enclosure and kept updated daily for the entire life of the subject. This is a document for internal use which is by far more articulated and detailed than a personal history file as imposed by the law for non-human primates. In particular, all the animals included in a procedure, even if only during the training phase, interact with or are observed by at least one experimenter or technician who works daily with the animals. This trained personnel can easily detect and record any possible deviation from normal conditions and optimal well-being, in addition to information such as the quantity and type of food and liquids consumed by the animal, the possible non-invasive measurement of body weight (for animals that get into the chair or box, for example), particular events or unusual behaviors to be noted, the type of enrichment provided and possible animal’s reluctancy to interact with it, as well as any qualitative and quantitative information concerning the performance of the animal in the training. This information also allows us to modulate and optimize the training procedures, adapting them to the characteristics of the individual animal. |

|

References

[1] F. Caruana et al., “Decomposing Tool-Action Observation: A Stereo-EEG Study,” Cereb. Cortex, vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 4229–4243, Aug. 2017.

[2] G. Buzsáki et al., “Tools for Probing Local Circuits: High-Density Silicon Probes Combined with Optogenetics,” Neuron, vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 92–105, 2015.

[3] P. Tovote, J. P. Fadok, and A. Lüthi, “Neuronal circuits for fear and anxiety,” Nat. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 16, p. 317, May 2015.

[4] P. K. A. et al., “Why primate models matter,” Am. J. Primatol., vol. 76, no. 9, pp. 801–827, Aug. 2014.

[5] K. J. H., “The evolution of brains from early mammals to humans,” Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 33–45, Nov. 2012.

[6] E. Borra, M. Gerbella, S. Rozzi, and G. Luppino, “The macaque lateral grasping network: A neural substrate for generating purposeful hand actions,” Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., vol. 75, pp. 65–90, 2017.

[7] J. Fooden, “Systematic review of the rhesus macaque, Macaca mulatta (Zimmermann, 1780).,” FieldianaZoology, vol. 96, pp. 1–180, 2000.

[8] H. D. L., B. Eliza, V. Jessica, M. Brenda, and C. John, “Laboratory rhesus macaque social housing and social changes: Implications for research,” Am. J. Primatol., vol. 79, no. 1, p. e22528, Dec. 2016.

[9] A. Calapai et al., “A cage-based training, cognitive testing and enrichment system optimized for rhesus macaques in neuroscience research,” Behav. Res. Methods, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 35–45, Feb. 2017.

[10] C. R. Ponce, M. P. Genecin, and M. S. Livingstone, “Automated chair-training of rhesus macaques,” J. Neurosci. Methods, vol. 263, pp. 75–80, 2016.

[11] G. E. Laule, M. A. Bloomsmith, and S. J. Schapiro, “The Use of Positive Reinforcement Training Techniques to Enhance the Care, Management, and Welfare of Primates in the Laboratory,” J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 163–173, Jul. 2003.

[12] S. J. Schapiro, M. A. Bloomsmith, and G. E. Laule, “Positive reinforcement training as a technique to alter nonhuman primate behavior: Quantitative assessments of effectiveness,” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, vol. 6, no. 3. pp. 175–187, 2003.

[13] A. L. Fernström, H. Fredlund, M. Spångberg, and K. Westlund, “Positive reinforcement training in rhesus macaques-training progress as a result of training frequency,” Am. J. Primatol., vol. 71, no. 5, pp. 373–379, 2009.

[14] L. Scott, P. Pearce, S. Fairhall, N. Muggleton, and J. Smith, “Training nonhuman primates to cooperate with scientific procedures in applied biomedical research,” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, vol. 6, no. 3. pp. 199–207, 2003.

[15] F. Barz et al., “Versatile, modular 3D microelectrode arrays for neuronal ensemble recordings: From design to fabrication, assembly, and functional validation in non-human primates,” J. Neural Eng., vol. 14, no. 3, 2017.

[16] A. Kohn, “Visual Adaptation: Physiology, Mechanisms, and Functional Benefits,” J. Neurophysiol., vol. 97, no. 5, pp. 3155–3164, May 2007.